Norsemen

The Vikings (from Old Norse víkingr, also known as Norsemen or Northmen) were seafaring north Germanic people who raided, traded, explored, and settled in wide areas of Europe, Asia, and the North Atlantic islands from the late 8th to the mid-11th centuries. The Vikings employed wooden longships with wide, shallow-draft hulls, allowing navigation in rough seas or in shallow river waters. The ships could be landed on beaches, and their light weight enabled them to be hauled over portages. These versatile ships allowed the Vikings to travel as far east as Constantinople and the Volga River in Russia, as far west as Iceland, Greenland, and Newfoundland, and as far south as Nekor. This period of Viking expansion, known as the Viking Age, constitutes an important element of the medieval history of Scandinavia, Great Britain, Ireland, Russia, and the rest of Europe.

The Vikings were known as Ascomanni, ashmen, by the Germans, Lochlanach (Norse) by the Gaels and Dene (Danes) by the Anglo-Saxons.

The Slavs, the Arabs and the Byzantines knew them as the Rus' or Rhōs, probably derived from various uses of rōþs-, i.e., "related to rowing" or derived from the area of Roslagen in east-central Sweden, where most of the Vikings who visited the Slavic lands came from. Archaeologists and historians of today believe that these Scandinavian settlements in the Slavic lands formed the names of the countries Russia and Belarus. The modern day name for Sweden in several neighboring countries is possibly derived from rōþs-, Ruotsi in Finnish and Rootsi in Estonian.

The Slavs and the Byzantines also called them Varangians (ON: Væringjar, meaning sworn men from var- "pledge, faith," related to Old English wær "agreement, treaty, promise," Old High German wara "faithfulness"). Scandinavian bodyguards of the Byzantine emperors were known as the Varangian Guard.

The Viking Age

The Viking Age of Scandinavian history refers to the period of time from the earliest recorded raids in the 790s until the Norman conquest of England in 1066. Vikings used the Norwegian Sea and Baltic Sea for sea routes to the south. The Normans were descended from Danish and Norwegian Vikings who were given feudal overlordship of areas in northern France—the Duchy of Normandy—in the 10th century. In that respect, descendants of the Vikings continued to have an influence in northern Europe. Likewise, King Harold Godwinson, the last Anglo-Saxon king of England, had Danish ancestors.

Geographically, a Viking Age may be assigned not only to Scandinavian lands (modern Denmark, Norway and Sweden), but also to territories under North Germanic dominance, mainly the Danelaw, including Scandinavian York, the administrative center of the remains of the Kingdom of Northumbria, parts of Mercia, and East Anglia. Viking navigators opened the road to new lands to the north, west and east, resulting in the foundation of independent settlements in the Shetland, Orkney, and Faroe Islands; Iceland; Greenland; and L'Anse aux Meadows, a short-lived settlement in Newfoundland, circa 1000. Many of these lands, specifically Greenland and Iceland, may have been originally discovered by sailors blown off course.[citation needed] They also may have been deliberately sought out, perhaps on the basis of the accounts of sailors who had seen land in the distance. The Greenland settlement eventually died out, possibly due to climate change. Vikings also explored and settled in territories in Slavic-dominated areas of Eastern Europe, particularly the Kievan Rus. By 950 these settlements were largely Slavicised.

Important trading ports during the period include Birka, Hedeby, Kaupang, Jorvik, Staraya Ladoga, Novgorod, and Kiev.

Generally speaking, the Norwegians expanded to the north and west to places such as Ireland, Scotland, Iceland, and Greenland; the Danes to England and France, settling in the Danelaw (northern/eastern England) and Normandy; and the Swedes to the east, founding the Kievan Rus, the original Russia. Among the Swedish runestones mentioning expeditions overseas, however, almost half tell of raids and travels to western Europe. Also, according to the Icelandic sagas, many Norwegian Vikings went to eastern Europe. These nations, although distinct, were similar in culture and language. The names of Scandinavian kings are known only for the later part of the Viking Age. Only after the end of the Viking Age did the separate kingdoms acquire distinct identities as nations, which went hand-in-hand with their Christianization. Thus the end of the Viking Age for the Scandinavians also marks the start of their relatively brief Middle Ages.

Religon

The Old Norse religion was an wide spread belief system that hosted a wide menagerie of gods and goddesses. The practitioners probably did not have a name for their religion until they came into contact with outsiders or competitors. Therefore, the only titles bestowed upon Norse religion are the ones which were used to describe the religion in a competitive manner, usually in a very antagonistic context. Some of these terms were hedendom (Scandinavian), Heidentum (German), Heathenry (English) or Pagan (Latin). A more romanticized name for Norse religion is the medieval Icelandic term Forn Siðr or "Old Custom".

The Germanic tribes rarely or never had temples in a modern sense. The blót, the form of worship practiced by the ancient Germanic and Scandinavian people, resembled that of the Celts and Balts; it could occur in sacred groves. It could also take place at home and/or at a simple altar of piled stones known as a hörgr.

However, there seems to have been a few more important centres, such as Skiringsal, Lejre and Uppsala. Adam of Bremen claims that there was a temple in Uppsala with three wooden statues of Thor, Odin and Freyr, although no archaeological evidence to date has been able to verify this.

Devotion to deceased relatives was a mainstay in Norse religion. Ancestors constituted one of the most ancient and widespread types of deity worshipped in the Nordic region. Although most scholarship focuses on the larger community's dedication to more fantastic gods and myths of the Vikings, it is understood that some sort of ancestor worship was probably an element of the private religious practices of the farmstead and village.[8] Often in addition to showing adoration to the standard Nordic gods, warriors would toast to “their kinsmen who lay in barrows”.

One Viking custom was to bury dead lords in their ships. The dead man’s body would be carefully prepared and dressed in his best clothes. After this preparation, the body would be transported to the burial-place in a wagon drawn by horses. The lord’s favorite horses and often, a faithful hunting-dog, were killed to be buried with the deceased man. The man would be placed on his ship, along with many of his most prized possessions. The Vikings firmly believed that the dead man would sail to the after-life.

Sacrifice could comprise inanimate objects, animals or humans. Amongst the Norse, there were two types of human sacrifice; that performed for the gods at religious festivals, and retainer sacrifice that was performed at a funeral.

Nordic peoples recognized a range of spirits dwelling in particular objects and places, such as trees, stones, waterfalls, lakes, houses, and small handmade idols. As agriculture developed in the Nordic communities so did the use of agricultural deities. As Norse life depended more and more on the factors that affected their crops, they began to dedicate more time to the deities that they believed had control over the weather, seasonal cycle, crops, and other agricultural aspects. Gods such as Freyr were portrayed as having control over the weather and being a commander of fertility amongst the crops.

Similar to many other societies the pre-Christian Viking religions also took interest in the eventual resting place of the dead. The Norse held so much dedication that went into making sure that the dead were cared for properly so that they could enjoy their resting place after death.

The use of ghost lore (referred to as Draugr) in the sagas is characteristic of the Norse lore and is directly connected to proper burial practices. Ghosts are portrayed as menacing physical presences that intend to injure the living and haunt them. The Laxdæla saga portrays how hauntings often take a menacing and ill hearted turn. These accounts of hauntings and menacing ghosts are often solved through proper burial practices. Burial customs are the primary explanation and solution of the problems faced by ghosts.

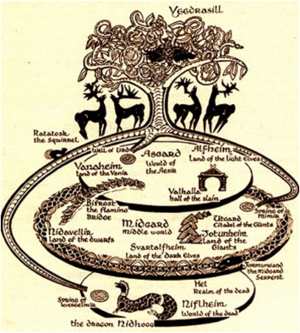

Odinn and Thor are considered the most popular of the Norse gods especially to warriors. Odinn is the god of victory and death, the Allfather, and King of the Gods. Odinn dwells in Valhalla, a great hall, where all those slain in battle feast and fight until Ragnarok, the Doom of the Gods, when they will storm out of the hall and fight at Odinn's side. Odinn sends Valkyries to guide warriors through battle. When a warrior is in his prime, Odinn betrays him and so he is slain. But this in not a curse but rather the greatest blessing to the fallen warrior. For Valkyries will now carry him to Valhalla. Thor is also a god of war and is considered the greatest warrior among the gods. He often journeys to Jotunheim where he crushed the skulls of giants with his mighty hammer Mjolnir. Warriors would often wear hammer pendants as a sign of reverence to Thor.

Festivals were a public celebration of the divine, where the local community or the nation renewed its bonds through shared worship. There were many elements to the Norse festivals, and it depended on which particular festival was being celebrated. Religious sacrifice was just one element of such festivals and holidays. The festivals were more so a place to celebrate one’s communal identity than to gather in a religious capacity.[20] This sense of the communal is underlined by the role of the local leader, whether king, chieftain or householder, in leading the rite. These celebrations also served to reinforce the social bonds between the chieftain and his followers, joining everyone in a single community.

Runes and Runestones

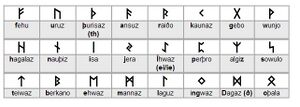

In Norse mythology, the runic alphabet is attested to a divine origin (Old Norse: reginkunnr). In the Poetic Edda poem Rígsþula another origin is related of how the runic alphabet became known to humans. The poem relates how Ríg, identified as Heimdall in the introduction, sired three sons (Thrall (slave), Churl (freeman), and Jarl (noble)) on human women. These sons became the ancestors of the three classes of humans indicated by their names. When Jarl reached an age when he began to handle weapons and show other signs of nobility, Rig returned and, having claimed him as a son, taught him the runes. The Viking peoples could read and write and used a non-standardized alphabet, called runor, built upon sound values. While there are few remains of runic writing on paper from the Viking era, thousands of stones with runic inscriptions have been found where Vikings lived.

The majority of runic inscriptions from the Viking period are found in Sweden and date from the 11th century. The oldest Stone with runic inscriptions was found in Norway and dates to the 4th century, suggesting that runic inscriptions predate the Viking period. Many runestones in Scandinavia record the names of participants in Viking expeditions.

The Elder Futhark, used for writing Proto-Norse, consists of 24 runes that often are arranged in three groups of eight; each group is referred to as an Ætt. Each rune had a name, chosen to represent the sound of the rune itself. The names are, however, not directly attested for the Elder Futhark themselves. The Elder Futhark was popularly used from the 2nd to 8th centuries before it evolved most likely due to new sounds being introduced to the Norse way of speaking during the Viking expansion.

The Younger Futhark, also called Scandinavian Futhark, is a reduced form of the Elder Futhark, consisting of only 16 characters. They are found in Scandinavia and Viking Age settlements abroad, probably in use from the 9th century onward. They are divided into long-branch (Danish) and short-twig (Swedish and Norwegian) runes. The difference between the two versions is a matter of controversy. A general opinion is that the difference between them was functional; i.e. the long-branch runes were used for documentation on stone, whereas the short-branch runes were in everyday use for private or official messages on wood.

There is some evidence that, in addition to being a writing system, runes historically served purposes of magic. In medieval sources, notably the Poetic Edda, the Sigrdrífumál mentions "victory runes" to be carved on a sword, "some on the grasp and some on the inlay, and name Tyr twice." The runes would be carved into the sword while chanting imbuing the weapon with great power.

Historically it is known that the Germanic peoples used various forms of divination and means of reading omens. Tacitus gives a detailed account (98AD):

"They attach the highest importance to the taking of auspices and casting lots. Their usual procedure with the lot is simple. They cut off a branch from a nut-bearing tree and slice it into strips these they mark with different signs and throw them at random onto a white cloth. Then the state's priest, if it is an official consultation, or the father of the family, in a private one, offers prayer to the gods and looking up towards heaven picks up three strips, one at a time, and, according to which sign they have previously been marked with, makes his interpretation. If the lots forbid an undertaking, there is no deliberation that day about the matter in question. If they allow it, further confirmation is required by taking auspices."

It is often debated whether "signs" refers specifically to runes or to other marks; both interpretations are plausible and Tacitus does not give enough detail for a definite decision to be made.

In addition to the runes there are a collection of rune staves that when carved or drawn in the appropriate manner and place have different powers. There are staves to attract lovers, give luck, protect locks, and for the warrior inspire courage or frighten enemies.

Seiðr and Galdr

Seiðr (sometimes anglicized as seidhr, seidh, seidr, seithr or seith) is an Old Norse term for a type of sorcery which was practised in Norse society. Seiðr practitioners were of both genders, although females are more widely attested, with such sorceresses being variously known as vǫlur, seiðkonur and vísendakona. There were also accounts of male practitioners, known as seiðmenn, but in practising magic they brought a social taboo, known as ergi, on to themselves, and were sometimes persecuted as a result. In many cases these magical practitioners would have had assistants to aid them in their rituals.

Seiðr was associated with both the god Oðinn, a deity who was simultaneously responsible for war, poetry and sorcery, as well as the goddess Freyja, a member of the Vanir who was believed to have taught the practice to the Æsir. Loki accused Oðinn of practising seiðr, condemning it as an unmanly art (ergi). A justification for this may be found in the Ynglinga saga, where Snorri opines that following the practice of seiðr rendered the practitioner weak and helpless.

One possible example of seiðr in Norse mythology is the prophetic vision given to Oðinn in the Vǫluspá by the vǫlva after whom the poem is named. Her vision is not connected explicitly with seiðr; however, the word occurs in the poem in relation to a character called Heiðr (who is traditionally associated with Freyja but may be identical with the vǫlva).[12] The interrelationship between the vǫlva in this account and the Norns, the fates of Norse lore, is strong and striking.

Like Oðinn, the Norse goddess Freyja is also associated with 'seiðr' in the surviving literature. In the Ynglinga saga (c.1225), written by Icelandic poet Snorri Sturluson, it is stated that seiðr had originally been a practice among the Vanir, but that Freyja, who was herself a member of the Vanir, had introduced it to the Æsir when she joined them.

Galdr (plural galdrar) is one Old Norse word for "spell, incantation", and which was usually performed in combination with certain rites. It was mastered by both women and men. The incantations were composed in a special meter named galdralag. A practical galdr for women was one that made childbirth easier,[2] but they were also notably used for bringing madness onto another person such as a berserker. Moreover, a master of the craft was also said to be able to raise storms, make distant ships sink, make swords blunt, make armour soft and decide victory or defeat in battles.

Both types of Norse magic are practiced in modern Asutru pagan revivals.

Viking Ships

Viking longships were the epitome of Scandinavian naval power at the time, and were highly valued possessions. They were often owned by coastal farmers and commissioned by the king in times of conflict, in order to build a powerful naval force. While longships were used by the Norse in warfare, they were troop transports, not warships. In the tenth century, these boats would sometimes be tied together in battle to form a steady platform for infantry warfare. They were called dragonships by enemies such as the English because they had a dragon-shaped prow.

The longship appeared in its complete form between the 9th and 13th centuries. The character and appearance of these ships have been reflected in Scandinavian boat-building traditions until today. The average speed of Viking ships varied from ship to ship but lay in the range of 5–10 knots and the maximal speed of a longship under favorable conditions was around 15 knots.

Viking ships varied from others of the period, being generally more seaworthy and lighter. This was achieved through use of clinker (lapstrake) construction. The planks from which Viking vessels were constructed were rived (split) from large, old-growth trees—especially oaks. A ship's hull could be as thin as one inch (2.5 cm), as a split plank is stronger than a sawed plank found in later craft.

Working up from a stout oaken keel, the shipwrights would rivet the planks together using wrought iron rivets and roves. Ribs maintained the shape of the hull sides, but were not intended to provide strength to the hull. Each tier of planks overlapped the one below, and waterproof caulking was used between planks to create a strong but supple hull.

Remarkably large vessels could be constructed using traditional clinker construction. Dragon-ships carrying 100 warriors were not uncommon.

Furthermore, during the early Viking Age, oar ports replaced rowlocks, allowing oars to be stored while the ship was at sail and to provide better angles for rowing. The largest ships of the era could travel five to six knots using oar power and a hasty ten knots under sail.

Weapons and Armor

Our knowledge about arms and armor of the Viking age is based on relatively sparse archaeological finds and pictorial representation.

According to custom, all free Norsemen owned weapons, as well as carried them at all times. These arms were also indicative of a Viking's social status. A wealthy Viking would have a complete ensemble of a helmet, shield, chainmail shirt, and animal-skin coat, among various other armaments.

The spear and shield were the most basic armaments of the Viking warrior. Other common weapons were the axe and seax knife. The seax knife was a long knife or short sword many Norse would wear horizontally on the back of their belt. It was a practical utility knife as well as a good close-quarters weapon. The sword was a very rare and powerful item reserved for huscarls and royalty. Another common and very symbolic weapon of the Norse was the axe - from the short throwing axe to the two-handed Dane axe. Few weapons were as versatile and well received. Vikings were relatively unusual for the time in their use of axes as a main battle weapon. The Húscarls, the elite guard of King Knut (and later of King Harold II) were armed with two-handed axes that could split shields or metal helmets with ease.

Bows were used in the opening stages of land battles and at sea, but they tended to be considered less "honourable" than a melee weapon.

Many Vikings had ancestral weapons, passed down through generations. Some were the famous Ulfberht swords forged from a near magical quality steel that was unseen in Europe again until the Industrial Revolution. Such ancestral weapons (axes, swords, spears even) would have names like Hrunting or Gram. During forging animal bones from a bear or wolf or even the bones of a dead ancestor would be added to the iron giving it greater strength and magical power. In addition "victory runes" would be carved into the hilt or blade while chanting to increase its power further. After a warrior fell in battle it was common custom to bend their swords and break their shields so they could not be manipulated by the angry spirit of the dead.

An ideology of warfare and violence motivated the Vikings, focused on the gods Porr and Odinn, the god of war and death. In combat the Vikings are believed to have engaged in a disordered style of frenetic, furious fighting, leading them to be termed berserkers. They may have induced this mental state through ingestion of materials with psychoactive properties, such as the hallucinogenic mushrooms, Amanita muscaria, or massive amounts of alcohol.

Fighting Tactics

There are many misconceptions of how a Viking fought. Many thought they were simple minded berserkers who charged hastily into the fray without hesitation. Although it is true that some men were berserkers and indeed Vikings fought without fear of death, that does not mean they sought for it. If a Viking could escape a trap and live to fight and possibly defeat his enemy on another day, that Viking would do so. But, if Odin betrayed them, they would see no escape and go down with sword in hand slaying all he could before being defeated. The Vikings believed Odin sent Valkyries to guide them through battle and that no matter what, Odin fates them to either live or die in the fight. If Odin brings them safely to victory then it was not yet that warriors time to journey to Asgard. But when Odin betrays them, it is a complement and blessing. For that means that warrior is in his prime and Odin requires him for Ragnarok - the doom of the gods.

Viking armies would be arranged by band, each warrior fighting mostly for his war chief - although that chief may have sworn allegiance to a jarl or king. Armies would post up on opposite sides of the field and yell insults at each other. Individual warriors would take this time to challenge opponents to single combat. Often these duels would be to resolve a previous grievance. If these displays of war were not enough the armies would begin to launch many volleys of arrows and other missile weapons at each other. The huscarls and hirdmen of the chiefs would form a shieldberg (like a roman testudo formation) around them to protect them. This is where most battles ended with both sides moving on to bigger and better things. But if the insults were good or the leaders of the armies hated each other enough the charge would sound. The men would form shield walls behind the banners. This served for mutual protection as well as to bolster moral. The pace would be set by the sound of axes beating on shields. Right before the lines met they would divide into a skirmish formation giving the men room to throw spears and swing their weapons. Fighting for a Viking was not the graceful dance of a samurai or the heavy sweeps of a medieval knight. They fought in a brutally fast hammering way meant to frighten the opponent and break their shield. Most deaths resulted from head or leg wounds. The leader of these armies would either be in the back yelling commands or (if he was a more courageous sort) seen fighting before his banner dealing two handed blows. One king fought a entire battle without any clothing on and without a shield. Vikings admired courage, and if a leader did not fight often and well that leader would find his army dissolved and routed.

Sea battles were much the same. Ships would use grappling hooks to pull themselves together. Planks that were laid across the deck would serve as the battle field. Spears and other long weapons such as the Dane axe would be used to stab / pull people into the water where they would sink due to the weight of armor. Other then these differences the battle would be much the same. The greatest prize following the battle would have been the ship. Ships were expensive and so sinking a ship in battle was considered a bad investment however strategic the act of doing so may be.

In general a Viking warrior fights primarily for personal glory. This results in a certain recklessness and lack of discipline - except in a nobleman's personal retinue. Courage and cunning were the weapons of a Nordic warrior on the field. Berserkers worked themselves into a rage before battle, but some think that they might have consumed drugged foods.

Berserkers

Berserkers (or berserks) were Norse warriors who are primarily reported to have fought in a nearly uncontrollable, trance-like fury, a characteristic which later gave rise to the English word berserk. The Úlfhéðnar (singular Úlfheðinn), another term associated with berserkers, mentioned in the Vatnsdœla saga, Haraldskvæði and the Völsunga saga, were said to wear the pelt of a wolf when they entered battle. Úlfhéðnar are sometimes described as Odin's special warriors: "[Odin’s] men went without their mailcoats and were mad as hounds or wolves, bit their shields...they slew men, but neither fire nor iron had effect upon them. In addition, the helm-plate press from Torslunda depicts a scene of Odin with a berserker—"a wolf skinned warrior with the dancer in the bird-horned helm, which is generally interpreted as showing a scene indicative of a relationship between berserkgang... and the god Odin"—with a wolf pelt and a spear as distinguishing features. There is a unit in Belegarth inspired by the legendary Úlfhéðnar called the Ulfserk Raiders.

King Harald Fairhair's use of berserker "shock troops" broadened his sphere of influence. Other Scandinavian kings used berserkers as part of their army of hirdmen and sometimes ranked them as equivalent to a royal bodyguard. It may be that some of those warriors only adopted the organization or rituals of berserk männerbünde, or used the name as a deterrent or claim of their ferocity.

Similarly, Hrolf Kraki's champions refuse to retreat 'from fire or iron.' Another frequent motif refers to berserkers blunting their enemy's blades with spells, or a glance from their evil eyes. This appears as early as Beowulf where it is a characteristic attributed to Grendel. Both the fire eating and the immunity to edged weapons are reminiscent of tricks popularly ascribed to Hindu fakirs.

In 1015, Jarl Eiríkr Hákonarson of Norway outlawed berserkers. Grágás, the medieval Icelandic law code, sentenced berserker warriors to outlawry. By the 12th century, organised berserker war-bands had disappeared.

Role Playing a Viking 101

So you want to be a Viking? That's good. We're under represented in Belegarth. Of course this means you'll have to represent Vikings appropriately. That means NO HORNED HELMETS!

Personality: Norsemen are lovers of song, the outdoors, sport, and good drink and food. Although welcoming and full of good will, Norsemen are dangerous when angered or insulted. On the battlefield they can be brutishly fierce to frighteningly cunning. Norsemen are resourceful and quick witted.

Norsemen look for strong leadership. If a leader was timid or weak in any way a Norse would abandon them. Viking chieftains often gifted their warriors with rings, weapons, armor, or other treasures in return for their service. However, in Belegarth you should look for a leader who allows personal freedom but is still strong and skilled in battle.

We Norse have the hearts of explorers and adventures and are difficult to tie down. Take a note from Odinn the Wanderer and see what other camps and units are about. The thirst of discovery can never be quenched.

Garb and Appearance: Norse men and women are tall, with blonde, red, or light colored hair and blue/green eyes. They are often bearded. If you do not fit this niche and want to be a Norseman more power to you.

In belegarth it is difficult to use strictly period materials. But if you can, you should make a linen or wool tunic and pants. If you have a tunic and pants then that's good enough. For armor Vikings wear chain or minimal leather plate. Pauldrons and bracers. If your persona is a rich Viking then a breast plate will work as well.

The present author would encourage you to customize your garb after a certain profession like hunting, fishing, or blacksmithing. This allows for personalization with a lower budget. Not every Norseman was a jarl. Embellishing your garb with runic writing and Nordic knot work is a good way to show your race off.

Weapons: Do whatever. Its belegarth.

Battle Rituals: Before battle it is customary to wash your face, clear out your nose, brush your hair and comb the beard using cold water. Then a healthy smearing of red blood (face paint) should be applied to the face and arms. Red is a color used to show hostile intent. After, a quick prayer and offering to whatever gods you hold is never a bad thing.

Keeping the gods: The present author is very devoted to the old gods of the North and so represents them on the field. Wearing Thor's hammers or other pegan pendants is a good way to show this devotion. However, if your Norse persona is of the Faith of the White Christ don't be afraid to wear a cross and defend that notion. Certain members of your kin may accept it, others may be ok with it, some might not care. Stand by the Nordic values of freedom and do what you want.

Norse on the other Races: Although Norseman are accepting of other people, we also aren't easy to trust or rely on others (including others of our kin unless bound by oaths of loyalty).

- Dwarves: share similar interests with Norsemen and trade is common, but due to their mischief among the gods they are kept at a distance

- Elves: small amounts of trade, general distrust, minimal contact

- Goblins: loathed, thought as weak,

- Trolls and Ogres: respected and feared, trolls are hunted and slain by heroes of the Norse

- Orks: somewhere in between goblins and trolls

- Skaven: vermin

- Gnolls/Bugbears/Werewolves/Dire Bears: slain for trophies, sometimes befriended

- Lizardmen and Kobolds: kept far away

- Birdpeople: easily killed and no threat

- Romans: Girly and to strict

- Scots, Celts, etc.: Good fighters and can make good allies

- Saxons, English: Fun to kill and raid. But can be a threat in large numbers.

- Knights: Worthy of respect. Revered as great warriors and may even be well liked if they conduct themselves with honor. Without honor, they are nothing.

Known Vikings in Belegarth

Feel free to add yourself.

Fehu

Grohiik

Halvard Stone-fist

Sif Inn Grárulfr

Nikoli Olafson

Remiros

Ravn the Skinner

Sigurd Amundson

Torvald Grimfate

Visund Alrikson

Vladimir Olafson

Recommended Reading

For those who want to learn more and have the time and energy, here are some helpful books.

The Northern Path by Douglass Dag Rossman

The Heimskringla by Snorre Sturlason

The Edda by Snorre Sturlason

Vikings: The North Atlantic Saga from Smithsonian Books

The Viking Art of War by Paddy Griffith

Sword Song by Sutcliff

Vikings a trilogy by Tim Severin